Urban oxidation flow reactor measurements reveal significant secondary organic aerosol contributions from volatile emissions of emerging importance

Recommended citation: Shah, R.U., Coggon, M.M., Gkatzelis, G.I., McDonald, B.C., Tasoglou, A., Huber, H., Gilman, J., Warneke, C., Robinson, A.L. and Presto, A.A., 2019. Urban oxidation flow reactor measurements reveal significant secondary organic aerosol contributions from volatile emissions of emerging importance. *Environmental Science and Technology*, 54(2), pp.714-725.

Psst! Scroll down for some behind the scenes content!

Abstract

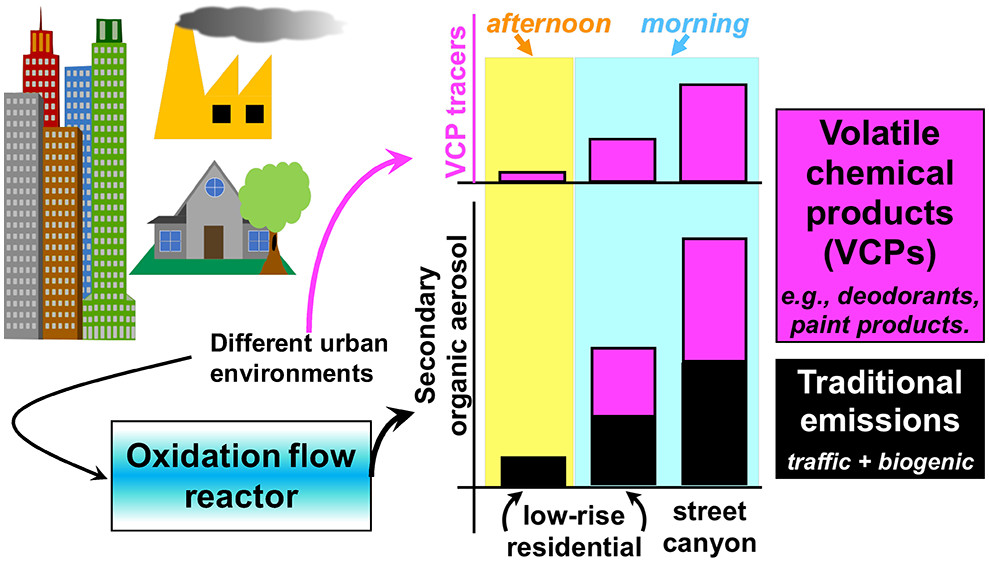

Mobile sampling studies have revealed enhanced levels of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) in source-rich urban environments. While these enhancements can be from rapidly reacting vehicular emissions, it was recently hypothesized that nontraditional emissions (volatile chemical products and upstream emissions) are emerging as important sources of urban SOA. We tested this hypothesis by using gas and aerosol mass spectrometry coupled with an oxidation flow reactor (OFR) to characterize pollution levels and SOA potentials in environments influenced by traditional emissions (vehicular, biogenic), and nontraditional emissions (e.g., paint fumes). We used two SOA models to assess contributions of vehicular and biogenic emissions to our observed SOA. The largest gap between observed and modeled SOA potential occurs in the morning-time urban street canyon environment, for which our model can only explain half of our observation. Contributions from VCP emissions (e.g., personal care products) are highest in this environment, suggesting that VCPs are an important missing source of precursors that would close the gap between modeled and observed SOA potential. Targeted OFR oxidation of nontraditional emissions shows that these emissions have SOA potentials that are similar, if not larger, compared to vehicular emissions. Laboratory experiments reveal large differences in SOA potentials of VCPs, implying the need for further characterization of these nontraditional emissions.

Behind the scenes

Figure 4 of this paper shows about 30 min of data collected by two instrumented vans driving alongside each other around a construction site in Pittsburgh. The NOAA van measured the amounts of different reactive organic gases (e.g., those emitted from deodorants, paints, etc.) in the air, while the Carnegie Mellon van oxidized this air to measure the reactivity of these gases.

Incidentally, this 30 min of sampling in Pittsburgh was just a test of whether or not this sampling strategy would work. Having gotten encouraging results, we next planned to apply this promising sampling strategy in populous parts of Manhattan e.g., Times Square, where the population density would be very high, and thus we would be able to observe a strong signal of personal care products.

We thus drove to New York City, and set up our base at the City College of New York main campus in Harlem. We started making detailed plans about how to perform our mobile sampling: we planned routes, we planned times of day to sample, we even planned a sampling route from Morristown, NJ to Stony Brook, NY (cutting right through Manhattan, of course), hoping to capture the rural-urban-rural gradient of various air pollutants.

And then, of course, the most vital instrument on the Carnegie Mellon van malfunctioned (the same instrument that also malfunctioned a year earlier in Oakland, CA). Unlike Oakland, however, we could not revive the instrument in time for the planned measurements this time. The NOAA van did make it to some of those planned drives, and they collected some wonderful data (published here)! I hope someone else gets an opportunity to do the measurements that I could not.

Fortunately, the data collected while we were stationary at our base station in Harlem proved immensely useful. These are the data are ended up being in this paper! And, while it was a much shorter road trip than the one from Pittsburgh to Oakland, I did manage to take a few pictures on the road: